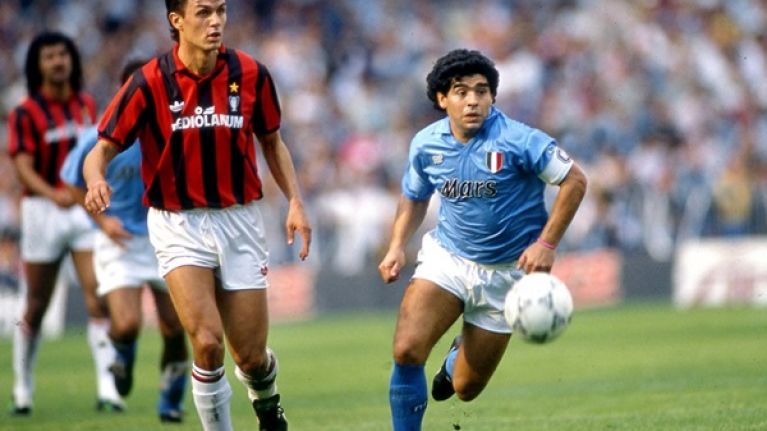

Diego Maradona: ‘The working-class boy from the shantytown signed with a legendary, down-at-heel team and helps them win their first championship.

Film Title: Diego Maradona

Director: Asif Kapadia

Starring: Diego Maradona

Genre: Documentary

Asif Kapadia is best known for documentaries Senna and Amy. It is no accident that he continues his look at troubled geniuses with a film that includes forename and surname in its title. On at least two occasions, the subject’s personal trainer notes that there is a difference between “Diego” (a man like many other men) and “Maradona” (a public figure who gained the status of indulged deity). “Diego has nothing to do with Maradona,” he says.

Amy Winehouse, as a pop star, was expected to further a public persona, but there was often too much of the inner woman on stage for comfort. Doomed to support his family from the age of 15, Maradona had little opportunity to develop as a human being. Work dominated, then drugs, women and spats with fickle fans. Maradona bossed Diego.

Kapadia’s house style is not well suited to explicit explorations of specific motivations. As in the earlier films, the images are all drawn from archival footage – the football often filmed muddily at pitch level – with sparse fresh interviews rendered only as audio; no talking heads are pressed for explanations as to why this mistake was made or how that triumph was achieved. We hear only a bit more from the current Maradona than we heard from the contemporaneous, deceased subjects of Amy and Senna.

Making fine use of an eclectic score by the Brazilian composer Antônio Pinto, Maradona works, rather, as a dizzying rush that (appropriately, considering the subject) showcases Kapadia’s most stylish film-making to date. Nowhere is this on better display than in an opening montage, scored to Giorgio Moroder-style throbs, which summarises Maradona’s journey towards the beginning of the film’s core story.

As an Englishman – currently a happy Liverpool supporter – Kapadia could be forgiven (or, at least, understood) for structuring his whole film around the notorious “Hand of God” goal in the 1986 World Cup. He does not do this. That famous match with England is covered and a voice notes that, by revealing both the cheat and the genius, it encapsulated much of what made Maradona an icon of his age.

But it’s the footballer’s time with SSC Napoli that forms the spine of the picture. What a story that is. The working-class boy from the shantytown signs with a legendary, but currently down-at-heel, team from the unglamorous south and helps them win their first championship.

The film gives the sense that the victory with Napoli meant almost as much to Diego as triumph in the World Cup. Sadly, he became involved with villains early on and, when things later turned sour, they assisted his slide into cocaine hell.

Though a little more discussion of Maradona’s technical proficiencies would be welcome, the film works as a celebration of the game’s intricate beauty. It also functions as a practical demonstration of its continuing idiocies. In later sections, the subject is compromised when Argentina are drawn to play Italy in Naples during the 1990 World Cup.

His provocative suggestion that the city is not really part of the wider Italy generates understandable hostility, but the apparent kickback for daring to score a penalty against the home nation just emphasises the illogical dynamics of fandom. All loyalty is provisional.

Oddly, we got closer to the hidden psyche in Kapadia’s films dealing with dead people. Maradona is still with us. He speaks while we watch his rise and fall. But he remains as unknowable as a figure from ancient myth. None of this dents the appeal of a film that makes brilliant use of his terrible, doomed momentum.

Our only serious complaint concerns the unnecessary, irrelevant and unkind inclusion of Ireland’s exit from Italia ‘90. You’re not winning any friends there, Asif.